The ballroom performance in Silver Spring promised to be an intimate show featuring two rising artists—an inventive Irish step dancer from Michigan scuffing alongside a versatile young bluegrass guitarist from Annapolis.

The near-capacity show last fall wasn’t at The Fillmore or the Quarry House Tavern or Takoma Station or any of the other local stages. The “ballroom,” as it was advertised through word of mouth, was in the neatly-appointed basement of a charming brick two-story colonial home near Sligo Creek.

The one-night-only performance by Nic Gareiss and Jordan Tice was a house concert, one of the many that play just about every weekend in homes and neighborhoods near you. While the idea isn’t new—having musicians in your house to entertain friends—house concerts have grown in popularity in recent years, thanks in part to technology that helps bring people together and a post-modern yearning for authenticity, connection and community.

“What I love about the house concert is that feeling of intimacy, like I’m getting to see something special, or rare, because there may only be 30 or 40 people in the audience,” said Andrea Cossettini, director of Washington, D.C.-based Percussive Dance Preservation Project, who organized the Silver Spring performance. “The barriers between performer and audience get blurry in this setting, I think. Because there’s no elevated stage or dramatic lighting, the performer can see and hear everything you as an audience member are doing, and it makes the event feel less formal, much more intimate.”

On any given weekend in Montgomery County, from Damascus to Takoma Park, there may be a dozen house concerts playing everything from traditional folk to pop. Finding a show can be fairly easy through Internet searches, which reveal a broad network of everything from matchmakers connecting bands with home venues, to single homes staging the occasional act. Gaining entry to a show can be as simple as buying admission online or dropping a “suggested donation” in a basket at the door. The process, however, can have a furtive speakeasy air, since hosts tend to withhold their addresses until guests commit to attend, and they generally prefer not to physically handle the money, which in most cases goes entirely to the performers.

“None of the hosts that I know are making money off of it,” said Scott Moore, of Rockville, who has been hosting concerts in his basement, family room and backyard since 1997. He said most house concert hosts are in it purely for the music and the community it cultivates, even if it means losing money to lure favored artists to put on a show. “It’s about a community of people that just so love the music and the scene and the vibe—and supporting arts and creativity and these people who are trying to make a living as performers and sharing their art,” said Moore, who books dozens of concerts a year through his Moore Music (In the House) series and is also president of Focus, a nonprofit that supports folk and acoustic music in the D.C. area.

The sentiments are echoed by Cheryl Kagan, the Maryland senator for Rockville and Gaithersburg who has been hosting house concerts for 14 years. She called hosting a time-consuming “money-loser” that is more than offset by the undertaking’s many rewarding intangibles, which she happily lists.

“I find great joy in it,” she said. “My favorite people come to my house and perform. And that’s pretty exciting. Second, I help to support artists’ careers and help them earn a living as singer-song-writers, which is a hard job.”

Kagan feels so strongly that “performers can afford to be musicians as their career” that her concert series, Folk ‘N Great Music, joined and contributes to the traveling musicians union (Local 1000) of the American Musicians Association.

“And the third reason I love doing this,” she said, “is after twisting your arm to come see a house concert, watching you be blown away by the high level of talent, by the intimacy of the venue, by the opportunity to meet and get to know the performer and feeling a real connection to the music.”

It used to be that artists would swing into town to play a concert hall or festival and then maybe pick up a private house concert for some walk-around money. But changes in the music industry—squeezing even the most successful artists’ profits—coupled with today’s sharing economy ethos (think Airbnb and Uber) have flipped that model on its head.

“What started out as filler gigs are turning into anchor gigs,” said Fran Snyder, a Florida-based singer-songwriter who runs Concerts in Your Home, an online portal where artists and hosts scope out each other’s profiles and look for a good match. The site pairs off about 2,000 events a year, mostly in the U.S.

“A lot of artists will tell you if it wasn’t for house concerts they wouldn’t tour at all,” Snyder said. “You not only get paid better because you’re not splitting the money with a venue that has a profit motive or a lot of overhead. But also you tend to be performing for not just music fans that have grown up with a culture of buying CDs after the show.” Hooking a few new young fans in a social media world can go a very long way.

“House concerts are showing themselves as an opportunity that has more and more advantages,” Snyder said.

That goes for hosts, artists and their guests. While artists collect proceeds from the door, and any CDs they might gently hawk during a post-show reception, there’s a lot more to be gained in performing live and unfiltered just few feet from your audience.

“When you play a house concert you can often see every face in the audience,” said Snyder, who counts the D.C. area as one of his favorite touring spots. “You can see when your ballads are moving somebody to tears or when somebody is falling out of their chair laughing. And you can start studying your performance craft almost like a comedian does. You can start working on your timing and your between-song patter.”

Scott Moore said that for guests the great appeal is the absence of distractions—none of the barroom chatter or clinking of glasses you might expect on the club scene. “That, to us, is the biggest thing,” said Moore, who with his wife Paula is a frequent guest at folk concerts. “Particularly for this type of music, they’re listening to every word and the lyrics really matter.”

The growth of house concerts has not gone unnoticed by established music halls, which have traditionally maintained a love-hate relationship with their small-time brethren. The house shows are a good training ground for artists who might one day be ready for the big stage with a ready-baked audience. The halls used to look the other way when an artist they billed also wanted to play a house concert while in town. Today, the economics of the marketplace have compelled promoters to draw the line.

“If someone says to me, ‘can I play a house concert in the D.C. market?’ nowadays I have to say no, much as my heart wants to say yes,” said Michael Jaworek, promoter for The Birchmere concert hall in Alexandria, Va. “I can’t do that anymore insofar as I need to sell every ticket I can. Those 30 or 40 people who might go to a house concert—I need those.”

If an act isn’t quite ready for The Birchmere’s 500-seat hall, Jaworek will still refer them to house concert facilitators like Moore. But in an era when people are upsizing their homes to accommodate larger house concert crowds, something has to give. “All of this does trickle down in a negative way where we can’t allow it anymore,” Jaworek said.

House concerts enjoy the luxury of being treated, in a legal sense, like Super Bowl parties, where you are welcome to invite as many people as you want to your house to watch the show, so long as you are not charging them to watch the television broadcaster’s intellectual property. Money collected at house concerts is usually a direct donation to the artists, so the hosts’ liability is limited, freeing them up to focus on making sure their guests and artists are having a good time.

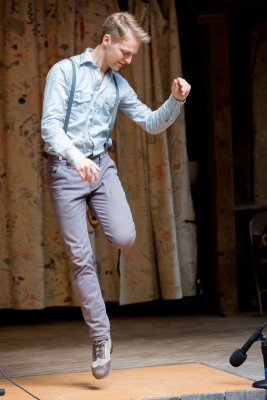

All that behind-the-scenes effort isn’t lost on Nic Gareiss, the Irish step dancer, who has performed nearly a dozen times in Montgomery County when he’s not performing around the world, or taking in a house concert on his travels. The intimacy of performing in someone’s home for their friends, he said, is about as real as it gets for artists.

“For me as a dancer, the house concert format allows folks to be very close to my moving, dancing body while I am working,” Gareiss said. “It also allows for the effort, the labor of performance—as manifest in perspiration, for example—to be visible in a way that a bigger stage might hide. This vulnerability can feel scary for a performer at first, but inevitably I think it allows for a richer experience for all.”