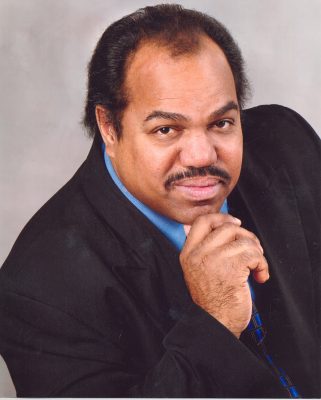

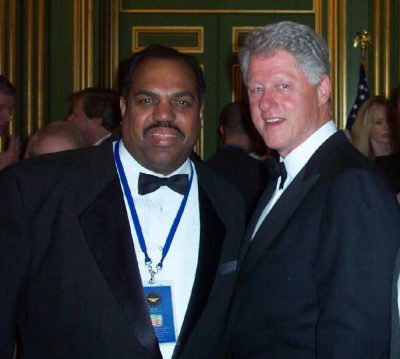

It has been 20 years since Daryl Davis shocked readers with his book “Klan-Destine Relationships: A Black Man’s Odyssey in the Ku Klux Klan.” The Grammy-winning musician from Silver Spring took readers with him on his journey to meet face-to-face with Klan leaders, neo-Nazis and other white-supremacists to ask what, exactly, they had against him.

“How can you hate me if you don’t even know me?” was his premise. And more often than not, it opened doors—if only a crack sometimes—that led to fascinating conversations and a few unlikely friendships. The book was less about generating heat and more about shedding light.

Now, two decades later as the country wrestles with a rise in racist rhetoric and a looming sense that things will not get better any time soon, Davis is once again calling on those who would disparage him because he’s black to meet with him and have a chat. This time, it’s the subject of an award-winning documentary, “Accidental Courtesy: Daryl Davis, Race & America,” which was released last month in select theaters in New York City and will air nationally on Feb. 13 on PBS. The film, which took honors at the 2016 SXSW Film Festival, takes viewers to a dozen cities across the country, from the recent violent flashpoints in Ferguson, Missouri, and Baltimore, Maryland, to the historic touchstones of Memphis, Tennessee, where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, and Washington, D.C., where Ben’s Chili Bowl still thrives as a survivor of the race riots that followed the civil rights leader’s 1968 murder.

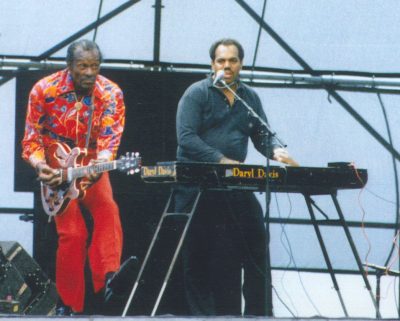

As always, Davis makes music a big part of his journey. He’s an accomplished keyboardist who has played with icons of American music, like Chuck Berry, B.B. King, Bo Diddley and Little Richard. It was music that first brought him in contact with the Klan: he was playing a country music gig in Frederick County in 1983 when he was approached by a stranger who expressed surprise that a black man could play piano like Jerry Lee Lewis. Davis went on to school the stranger (a card-carrying Klan member) on where Lewis picked up his groove—from black blues and boogie-woogie piano players. The chance meeting led to Davis’ introduction to the local KKK’s imperial wizard, Roger Kelly, who struck a bond with Davis and a few years later left the group.

That unlikely relationship is among several explored in the documentary, where Davis poses touchy questions in his characteristically disarming and charming way.

“What kind of music do you like?” Davis asks Jeff Schoep, leader of the National Socialist Movement, a white separatist group, during their first meeting in a Birmingham, Alabama diner. The ensuing exchange gives Davis an opening, which is what the documentary subtly implores viewers to do: find common ground and talk to each another.

“If you and I agree, I’m not accomplishing anything by trying to convince you of what you already know,” Davis said in the film. “The way you resolve that is you invite somebody to the table who disagrees with you, so you’ll understand why they have that point of view.”

Filmmaker Matt Ornstein and his crews spent about two years on the project, criss-crossing the country and tailing Davis on his busy tour routes. In an interview, Ornstein said he learned about Davis from a news story, then read his 1997 book. “Here was someone doing it differently,” he said. “And I wanted to know why he did it that way, how he did it that way, and what kind of results he got.”

Not everyone agrees with Davis’ hands-on approach to hate groups, as we see during a visit to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), an Alabama-based national nonprofit organization dedicated to combating hate and bigotry. Mark Potok, a senior fellow at SPLC, doesn’t mince words during a sit-down interview with Davis and Ornstein. “Our intention is, if possible, to destroy these groups,” Potok said. “If that’s not possible, to marginalize them politically.”

As the national narrative on racism has unfolded during the past few years, Davis said he’s not all that surprised at society’s lurching progress. “Our country is very slow when it comes to ideology,” he said in a recent interview. “It’s not that surprising that the message—how can you hate me if you don’t even know me?—is still being resonated and we still haven’t learned our lesson.”

Davis, meanwhile, will continue doing what he does best—playing his music and connecting with people. “As a band leader, it’s my job to bring harmony to the musicians,” Davis said. “So I carry that same thing when I’m offstage. I try to bring harmony between people and music is a common denominator.”

“Accidental Courtesy: Daryl Davis, Race & America” airs Feb. 13 on PBS and is also available for download on Amazon.

PBS Link: www.pbs.org/independentlens/films/accidental-courtesy/

Trailer: www.pbs.org/independentlens/videos/accidental-courtesy-trailer/

Website: http://accidentalcourtesy.com