His work is on display at the Mansion at Strathmore, but first-generation Irish-American lathe-turn artist Michael Brolly doesn’t romanticize the concept of “the mansion on the hill.” Indeed, “Walking History,” the large oak table he constructed and sand-blasted for the “Interiors” exhibit, is embellished with the symbols of his parents’ journey from poverty in Northern Ireland to service in America.

“There’s a cup and saucer at each setting,” he explained. “On one is an apron because my mother was a domestic, and the other has a chauffeur’s cap because my father was a chauffeur. That’s how they met.”

Brolly, who knew from day one of kindergarten that he would become an artist, first came to Strathmore in 2015 to participate in the “Women Chefs: Artists in the Kitchen” exhibit, portraying cooking consultant Mary Howley. Now he’s back as part of a show that just happens to run through Irish-American Heritage Month.

Lit from below and crafted in a style Brolly invented specifically for this purpose, the table offers symbols of Irish history and identity: bowls decorated with the crosses of the once-warring Irish Catholics and Protestants, and a chain-bound soup tureen and ladle that evoke the devastating potato famine of 1845-52 and the use of soup as a political tool.

“In the bottom of that soup tureen is a vanishing potato—move your head one way, you can’t see it; move the other way and it reappears,” he said. “That’s about the famine. And in the bottom of the ladle are two flying geese.”

That’s a reference to the exodus of Jacobite soldiers and officers led by Patrick Sarsfield to France in 1691, a military defection to the Continent that has since evolved into a euphemism for Irish emigration. It’s an image that inspired William Butler Yeats—his poem “September 1913” namechecks the wild geese who “spread grey wing on every tide”—and one that stayed with Brolly. “It’s all about the ghosts,” he said.

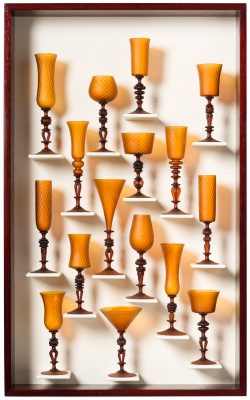

For this show, Brolly chose to imbue his work with ghosts, and other artists—most notably D.C.-based Michael Janis, who transformed old family photographs into a thrilling montage of translucent glass portraits—have also called upon family lore to generate art here. But “Interiors” features a curated selection of pieces that blurs the boundary between artistic and functional, and redefines what can be expressed through furniture and decoration.

“It’s about interpretation,” Strathmore curator Harriet Lesser said. “The lines are not so clearly drawn between art and craft anymore, and artists don’t want to be pigeonholed into a certain medium or a particular way of working.”

And “Interiors” celebrates that freedom, offering artists an opportunity to create a piece of furniture or interior decoration that is as much an art narrative as it is a utilitarian object. Lurking deep inside the objets d’art on display are practicality and whimsy, function and fantasy.

“Every place we are is an opportunity for art,” Lesser observed. “We’ve all expanded in that we don’t go out and buy matching furniture; we pick a piece that appeals for different reasons.”

The pieces in “Interiors” can be used as chairs, tables and light fixtures, yes—but they also can be art.

“We’re moving right along through history and culture,” Lesser pointed out. “People’s houses have become their own art space—and not just with what’s hanging on the wall. There are a lot of things here that are universal symbols that the artists have chosen to use in different ways.”

And so, North Carolina-based artist-blacksmith Elizabeth Brim creates steel pillows, inflating hot, hollow steel with compressed air (in a technique similar to glassblowing) to evoke soft, delicate forms in metal. Music photographer/fashion designer Rachel Warren creates a blanket using unspun wool she hand-painted to ensure specific colors and patterns. David Knopp uses the “strata” he finds in plywood to evoke the movement and flow of nature, and Janis “paints” with powders of pulverized glass to reimagine the concept of the family photo.

“It’s not a decoration,” said Lesser when asked to describe the art in the exhibit. “It’s not a ball on the Christmas tree—it’s much more integral than that.”

For Brolly, every component of his art is integral, deeply attached to a story that’ is at once specific and universal. Like the sugar bowl (a reminder of the creation of “afternoon tea” by a post-17th century British sugar industry, eager to drive up demand once its presence in the slave trade had lowered sugar’s production cost) embellished with a row of blackened teeth to illustrate the ripple effect of greed and consumerism. And like the plates that depict events and adventures in his own life, including his immigrant family’s stand against racism during the Civil Rights era. It was something he said they realized when his parents took the family back to Belfast in 1963, and compared the Irish Troubles to the racial prejudice they quietly accepted at home.

“Growing up in Philly, you could see that some people looked different—you could see it,” he said. “But then you go back (to Ireland) and everybody looks the same, but they still see differences. It was all so idiotic, like ‘What the heck?’

“And when we came back home, we saw that judging people by the color of their skin was idiotic, too. And we started speaking out”

For Brolly, art and personal politics inform every aspect of life. A teaching artist, he said he believes his students “are capable of anything. I actively work at staying out of their way—I help them express themselves; that’s my job.” He once gave a TEDX talk, “How Do We Say We Are Sorry: Singing to Whales,” about a wooden boat/musical instrument he and his students created to communicate with whales and apologize on behalf of human kind for their slaughter.

“I have a vast tool box of skills: I can teach,” he said.

And he has left a lesson about art, life and heritage–right there on the table.

Michael Brolly is one of several artists whose work is on display through April 2 in the “Interiors” exhibit at The Mansion at Strathmore, 10701 Rockville Pike, North Bethesda. Mansion hours are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday; 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Wednesday, and noon to 4 p.m. Sunday. An opening reception is scheduled for 7 p.m. Thursday, March 2; and on Saturday, March 4, a tour and talk for children (ages 7-plus, $5) starts at 10:15 a.m. and a curator’s tour for adults (free) at 1 p.m. Visit www.strathmore.org or call 301-581-5100. View this event on CultureSpotMC here.