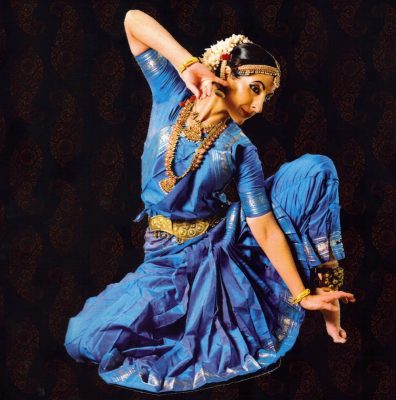

Nilimma Devi won the Lifetime Achievement Award in the 2013 County Executive’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts and Humanities. Four years later, the artist, educator and choreographer continues to create and achieve.

Devi is the founder and director of the Silver Spring-based Sutradhar Institute of Dance and Related Arts (SIDRA), which presents contemporary classical works in the Kuchipudi dance style from South India and focuses on creating “new alliances between musical genres and dance styles in feminine divinity, women’s issues and the environment.”

SIDRA’s professional dance company, Devi Dance Theater and Youth Ensemble, will perform “Stories in Movement” on Saturday, April 15, at the JCC in Rockville. In this concert, Devi said, “I would like my dancers to succeed in conveying to the audience something deeply truthful to themselves personally, and to the art form as sacred heritage. The story being told without words should be so emotive that it creates its own yearning and passion, lifting the one who is watching into their own feeling of soul.”

Devi graciously responded to CultureSpotMC’s questions about her life and her art.

When and why did you come to the U.S.?

In late 1968, as I was pursuing my dance training, I met an American Peace Corps volunteer. A courtship ensued and we were soon married. I came as a bride to the U.S. and settled in Madison, Wisc. I began at once the task of trying to adjust to a whole new world, while my husband embarked on a doctorate in Indian history. I had an offer at the University of Wisconsin to teach dance. My students taught me that learning was a two-way street!

When and where did you receive your training?

As a displaced refugee family, due to the partition of India and Pakistan, I saw firsthand the turmoil of culture and society when extreme politics became a fray. To me, dance was a source of intelligent learning, a sense of progress that offered such solace where there seemed to be chaos around me, and a way to strengthen my body in a joyous way. I pursued dance in various cities from the age of 6. My serious study was with a guru or teacher named Dr. Nataraja Rama Krishna in Hyderabad, India. I studied with him for a solid eight years and learned a great deal of the fundamentals of Kuchipudi technique.

Was dance a part of your upbringing?

I gravitated towards dance and theater as a young girl without needing any pushing from my parents. Rather, I began to beg for class. It was hard, I suspect, for my family to both grapple with the urgency of survival and at the same time pay attention to me. But I was single-minded. All I knew was that dance gave me a world to escape to from the constant chaos.

I remember that the stories of tragedies being passed around the little community—inescapable confirmations of the sorrowful faces I saw on the streets—would just ebb away when I learned a new step. Stamp, step, turn…now add a hand gesture with the fingers flaring out like the rays of the sun; these were my prescriptions.

My young body delighted in the demands made on it, too. I grew from being an underweight slip of a girl, who was teased mercilessly by my Punjabi cousins and aunties, to an athletic teenager. I don’t think it was class alone that did this magical transformation though. I was so fed up with the teasing that I mentally vowed to see myself as strong where others called me weak. I took to affirming my image as beautiful like the divine goddess Durga whenever I passed a mirror—no matter what I had heard in passing that day. My body shape, energy and entire constitution changed within two years. With my newfound robustness and stamina, I learned also never to give up or give in to another’s misperception.

Are there other dancers, musicians or artists in your family? Did your family encourage your interest in dance?

I come from a middle class urban family of Hindu persuasion. But within our family, there was a great feeling of tolerance for diversity of all kinds—religious, cultural, ethnic. My mother, Pushpa, was a most unusual woman. She was a deeply spiritual thinker. I recall she wanted me to dance. My aunt was also my champion and a very different sort of cheerleader. Both were vital, strong women in my life. When my family collectively decided it was best I stop dance given its poor reputation in society, I continued practicing secretly.

What led you to start your institute in 1988?

We came to Washington, D.C. as a diplomatic family, since my husband had joined the Foreign Service some years back and now was the time for our sabbatical in the U.S. We were supposed to go back overseas again after a three-year stint in the U.S. My heart was far from rejoicing at being back, however, since the marriage itself had begun to break. I was struggling to comfort our two teenage children, who knew without being told that things were bad. It was my dance and teaching that led me to a place of peace.

How has your work changed through the years?

Good art must not live in isolation. I continue to see that the diverse community has rich linguistic and cultural qualities that asked us to respond to them artistically with adapted works. The audiences needed to understand the ancient stories. I knew that while a traditional Telegu-speaking viewer would get the language and nuance of the form, this new demographic would see the same piece differently. I wanted to reach out to my audience and students in order to truly share the art form. But how? I needed to come up with strategies that were simple and evocative. So, I started with translating the Sanskrit. My daughter set the tone for what went on in the choreographic sessions in the studio, where she translated the poems into an English subtext.

A couple of years later, I added musical recordings that I did in Hyderabad with an English reading of the poetic meaning. Live actors—one of whom had Shakespearean training—came to the forefront for a Smithsonian performance, adding a dose of American humor to the aesthetic.

It was a heady feeling to get the audience to laugh or respond with awe. I knew this was the lifeline of communication. The audience is so important. Indian dance is so spiritual. To an Indian sensibility, it all makes sense to connect the curve of a hip and the mathematical circularity of Carnatic rhythm to the Infinite. But to a Western ear and eye, something needs to be added to explain all this to the expectant viewer. Otherwise, they are like a parachuter with no parachute, tumbling through the clouds of an artistic void. That is why art is ultimately a selfless act.

You have combined an ancient form of dance with yoga, creative writing, storytelling and music. Why did you develop such a form?

The poetry, mythology and ritual of India is deeply woven into classical dance. It is important to me to bring this to the focus each time I perform. Reading Carl Jung and psychologist D.W. (Donald) Winnicott helped me grasp the point of understanding because they emphasize (that) for an individual wholeness and healing, we must connect to a space within as well as be part of the community we live in.

What are your proudest accomplishments?

I am most grateful for my piece called “Gossamer of Soul” by the poet Kabir, a 16th century Muslim weaver, radical thinker and saint. I also feel endlessly glad for “Mahadevi Akka” with its influence of the 12th century woman poet and firebrand mystic. Mahadevi Akka was a woman who had the courage to leave her abusive husband, a king, and seek enlightenment. Her poetry about Shiva, the creator, is some of the most beautiful poetry ever written. Like the poet Kabir, some centuries later, she spared no hypocrisy—not creed, gender nor cast—in her work.

Finally, there is “Mandala”, a poem-based dance written by a Buddhist nun named Metticka whose feminist work stands out. Other works that bring such creative satisfaction are: “Goddess of Tides,” “Mother of Tears,” “From the Diary of Tears” and “Sita, Gentle Warrior.” Each one was its own journey of breaking free from norms, traditions and ideology.

What are your goals for the future?

My hope and aspiration is that the institute remains true to the mission it has embarked on: truth, sacred wisdom and timeless art. The name of the institute itself is a meaning that tides it forward—the “thread bearer” or Sutradhar. Linking audience, community and artist together is a noble, beautiful and loving task. The thread that connects us all is something I hope to always see cherished here at Sutradhar Institute of Dance and Related Arts.

“Stories in Movement,” by SIDRA’s Devi Dance Theater and Youth Ensemble, will begin at 3:30 p.m. Saturday, April 15, at the JCC’s Kreeger Auditorium, 6125 Montrose Road, Rockville. Tickets are $15, $20 at the door, $10 for children younger than 12. Call 301-593-2664 or visit http://dancesidra.org.