Beatriz del Olmo-Fiddleman sets an example for teenage immigrants struggling to adapt to their new lives and opportunities. Primary among the factors that make this possible is her intimate understanding of their experience; born and reared in Mexico, she, too, resettled in the United States.

“I identify with them, and that creates a bond,” said del Olmo-Fiddleman, who moved to San Diego, California, for her graduate work in 1999, and has lived in Gaithersburg’s Kentlands community for about five years. The mother of two Rachel Carson Elementary School students also works as a real estate agent for Coldwell Banker, where her manager Kelly Vezzi said she treats her clients with the same respect and professionalism as her students.

Although she grew up in a “conservative family”—one in which her parents believed that a woman’s place is in the home, del Olmo-Fiddleman wanted more. She embarked on that path with a bachelor of arts in graphic design from Anahuac del Sur University in her native Mexico City. When her application to study in the U.S. was approved, her parents told her she was crazy. “I have been there. I know how it feels to break traditions,” del Olmo-Fiddleman said, pointing out that she advises her students at Sherwood High School in Olney and Albert Einstein High School in Kensington to have a plan, whether that may be to return to their native country, pursue a college education or prepare for a specific career.

Del Olmo-Fiddleman proceeded to study at San Diego State University where she earned a master of fine arts in graphic design, was inducted into the Phi Beta Delta Honor Society for International Scholars—and met her future husband, whose work brought them to the Washington metropolitan area.

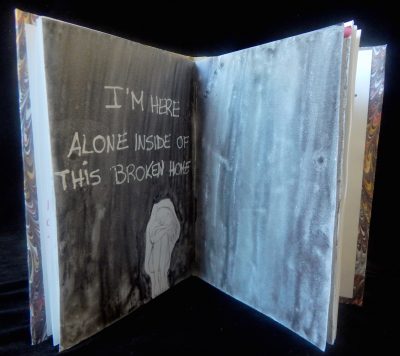

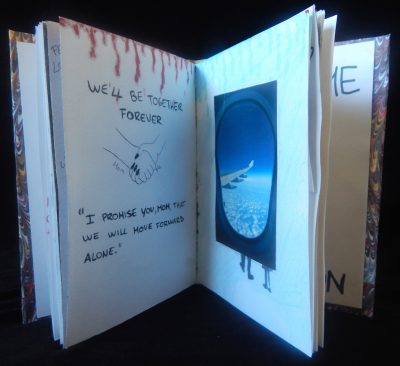

To make their books, the students, mostly ninth-grade Spanish speakers, used creative writing and/or visual narrative–like photographs and drawings when language was a barrier–as well as the bookbinding skills del Olmo-Fiddleman taught them. “Each student portrays their visual and narrative experience by the size and format of the book that matches their personality and journey,” she said, noting that telling the stories of their lives is “part of healing their trauma in a very informal but supportive and respectful school environment.”

This year’s exhibit of handmade books contained work that “was elaborate, detailed, personal and beautiful,” Forster said, noting that “So many of these students have real artistic talent that was cultivated through this process and all of them had the chance to express themselves in a new way.”

Forster said that visitors to the exhibit “were blown away with the struggles expressed, the depth of emotion and the resilience of these students.”

After reading the students’ books, Nestor Alvarenga, Latin American Community Liaison for the county’s Office of Community Partnerships, concurred. “I have felt proud, motivated, sad, empathetic and angry reading each of those stories,” he said. “The powerful artifact that Beatriz’s students bring into the community has not only enriched our knowledge of the journeys our youth have gone through; (but) also, these books are artistic, rich of color and folklore, and are full of feelings and emotions.”

“Beatriz is an exceptional artist and patient teacher, able to connect with students personally and help them open up through their artwork,” Forster concluded. “I think it’s an amazing outreach that Beatriz is doing, to share her artistic talent in a way that recognizes and hopefully empowers these students.”

The ESOL teachers at both high schools also have high praise for del Olmo-Fiddleman and her program. Aileen Coogan, at Sherwood, noted that at the start, “some students were reluctant to participate. Although they wanted to learn the bookbinding techniques, they didn’t all want to tell their stories.”

But del Olmo-Fiddleman’s demeanor changed that. “She was patient and kind and inspiring, sharing her artwork and her life story. The students enjoyed learning new techniques and having the freedom to express themselves, and the days she came to work with them became very calming ones. Some of my more challenging students became so involved in the creative process and their thoughts and their whole classroom behavior changed while they were working.”

“As Beatriz spent more and more time with the students, taking time to talk one on one with each child, she gradually won over even the most reserved of students,” Coogan said.

Coogan felt the program was “very therapeutic” for the students. “They began to share some stories—ones of children separated from their parents for 10 years or more, ones of violence, crime and fear, ones of losing or leaving behind loved ones, and ones of struggling in a new country, culture and language. Through this sharing, students not only unburdened a bit of the weight they carry inside, but also bonded more with their classmates realizing that many had challenging experiences. Students became more understanding and supportive of each other.”

During visits to the exhibits del Olmo-Fiddleman arranged–at Sandy Spring Museum, Silver Spring Library, Salvadoran Embassy and Glen Echo Park, Coogan said, “students were encouraged to speak up and share, and many did. They became prouder and more confident and realized that they had a voice and there were people who wanted to hear their stories.”

ESOL teacher Eva K. Sullivan, at Einstein, found the “meaningful self-expression” del Olmo-Fiddleman elicited from her students “awesome to watch.” In a “soft spoken and nonconfrontational (manner), she provides models, guides them step by step and is extremely encouraging and supportive with the reluctant students. Each participant walks away from her workshops with one or more works of art that make them feel proud.”

Sullivan was delighted that her students “found new meaning and purpose at school,” describing one boy who “became so enamored of art that he went out and purchased art supplies and began sketching outside of school. He would bring his work in to show Beatriz and me—and received a great deal of praise. This creative outlet and the positive attention that resulted gave him a boost of confidence that showed in his classwork. He went from being disengaged to thriving.”

The program “gives them a sense of community that they don’t get elsewhere,” Sullivan added. “Beatriz del Olmo-Fiddleman shows incredible patience, persistence and humor when dealing with traumatized students.”

As for del Olmo-Fiddleman, she is convinced of the value of her program. “I believe in the power of art and I believe in the power of self-expression. I teach with passion, compassion and motivation to inspire others to create art and to write their own storytelling.

“The body of work by the youth empowers their identity into a society that has restricted them to have a voice and a choice. Immigration should not be equal to rejection, it is just a location of events that each person has chosen to make choices, and perhaps, better future.”

Del Olmo-Fiddleman has applied for another grant, and expects a decision by the end of the month. Even if it doesn’t come through, the woman these ESOL students call “the book lady” knows she will find a way, another partnership, to continue with work that has become even more important in this political climate. “I do this because I love it,” she said.