This year celebrates the 13th annual Bethesda Painting Awards, a competition for painting—in in its widest possible definition—among artists from the Maryland, Virginia and Washington, D.C. region. Nearly 300 artists from all points in their careers submitted work that three local jurors judged.

The awards continue to be made possible by Carol Trawick whose credits as a community activist and philanthropist of the arts are of the highest order. At the awards ceremony and exhibit opening on June 7, Trawick’s short speech encapsulated her enduring love of both art and artists whom she sees as visionaries and their work as critical to our sanity in these chaotic times.

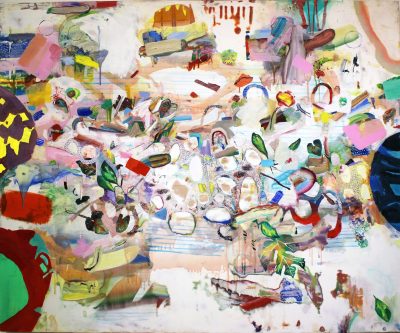

The top prize went to Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann. No stranger to these awards, she was a finalist in 2008 and 2009, and placed second in 2010 and third in 2012. Since then, her technique has evolved, although there is a consistent use of cut paper, collaged materials and layering of paint that were present in her earliest exhibited work. Mann works on a large scale, with some recent paintings on paper measuring some seven to eight feet in height and 20 to 30 feet in width. At this scale, paintings fill up the entire visual field of a viewer—as the artist says, simultaneously “pulling you in and pushing you away.”

Mann has said that she begins with a stain in the center of her very larger paper support, the “product of chance evaporation of ink and water.” Continuing to work on the floor, sometimes actually sitting in the painting, she coaxes that center outward, flinging or painting large swathes of acrylic color and moving it around the surface. The gestural process is reminiscent of the action painting of abstract expressionist artists like Jackson Pollock, as is the scale, and like Pollock, Mann feels at home physically inside her work.

Using bright color ranges, whether in blue/green or red/pink/purple combinations, the work embodies the energy of Mann’s gesture. Yet that energy is overlaid with delicate sumi ink passages of flower and plant forms that are either drawn directly, applied as collage or silkscreened onto the surface. The flowing organic lines and gestural splatters make one think of land or seascapes. The work, “Spaniel,” has more connotations of the latter, with a great white form in the center like a crashing wave.

Collaged surfaces were something of a theme in this year’s finalists. Amy Boone-McCreesh’s exuberant collages explode with colorful forms and found objects layered and pasted on paper supports.

Similarly, Frank Cole’s multimedia dark meditations on the crisis in the environment include attached wood or brass forms, while the whimsical works of Mike McConnell’s “Trout Fishing in America” series are composed of painted cut-paper elements arranged in tightly patterned compositions. Second-place winner Carolyn Case’s paintings on panel, have a heavy, overworked feeling. She wrote about them, rather inscrutably, as reflecting her fascination with the idea of “homemade tattoos” connotive of someone “desperate to express themselves, and…the scratchy tender aesthetics of this.” Like tattoos, Case creates imagery using tiny dots that might originate in her interest in embroidery and textiles. The stratified layering effect also betrays the fact that the artist treats her works almost like excavations, sanding down areas and repainting them—sometimes for as long as two years.

Third place went to Kenneth Schiano, a painter whose work mirrors the fact that he is a working architect. Although he earned a bachelor of arts in architecture at Cooper Union, he is largely self-taught as a visual artist. His small-scale paintings on panel have a constructed look, almost as though they, too, were collages. Reflecting “architectonic principles” the work is abstract, with echoes of Paul Klee and even of the geometry of medieval manuscripts or stained glass.

Schiano has a professed interest in the 14th century Italian Gothic fresco painter Giotto. This may be seen in his sharp outlines and the flatness of his dry pigment/wax surfaces, enlivened occasionally with what looks like metal leaf. While clearly interacting with older art, Schiano calls himself an “outsider,” a nonconformist to the narrative of art history. The series represented in the exhibit is titled “The History of Art in Dyssynchronos Order,” with each panel referred to as a “fig.” The convention is commonly used in art history texts to refer to “figures” or illustrations. Therefore, while confessing his battle with art history, and especially with the contemporary scene, Schiano, like everyone else, can’t escape either.

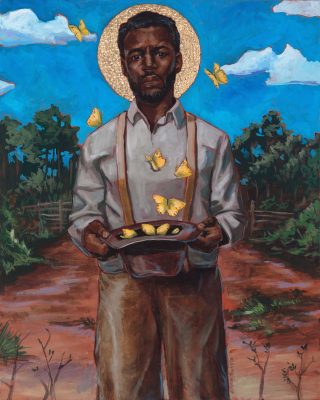

There was no “younger artist” winner this year, but two of the finalists are in the early stages of their careers. Both are figurative painters, although their sources are very different. Stephen Towns grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, and has found visual inspiration in medieval and early Renaissance painting, as well as in African American quilts and textiles. He mentions that he became aware that about 40 percent of enslaved Africans brought to the U.S. passed through his hometown during the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and the historical remnants of slavery were vivid for him there. Yet, moving to Baltimore to attend the Maryland Institute College of Art, he began to see the harsh reality of urban poverty and violence as a legacy of that “peculiar institution” that had somehow seemed softened by the South’s lush landscape. His paintings in oil on canvas feature figures with gold-leaf halos, and iconography that reflects both African-American Christian spirituality and slavery’s painful history. They are striking and memorable images, with titles like “The Righteous and the Wise” and “Their Works are in the Hand of God.”

Trevor Young’s large square paintings capture the modern urban scene in a completely different sensibility. Borrowing a term from author Marc Augé’s “Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity” (1995), Young calls his current subjects Non-Places, seeing them as quintessentially American. The aesthetic of “ugliness and convenience” they represent has become global, and is present very nearly everywhere. However, isolated and illumined with strong contrasts of light and dark, these same constructions take on a different kind of beauty, even a sense of mystery. This is especially evident in “Bluest Vapor,” his smoky rendering of a gas station in blue tones against an almost black surrounding, as if the usual pumps under a canopy were something exotic and notable. Something about this painting is reminiscent of the surrealist René Magritte in the particularity of the lighting and the feeling of enigma that emerges from removing the subject from its ordinary context.

The Bethesda Painting Awards exhibit will be on view through July 1 at Gallery B, 7700 Wisconsin Ave., Suite E, Bethesda. Gallery hours are Wednesday through Saturday, noon to 6 p.m. Call 301-215-6660 or visit www.bethesda.org.