Founded as a Quaker community, Sandy Spring became a place of refuge for people seeking religious tolerance and fleeing slavery. Today, the Sandy Spring Museum continues that heritage by showcasing the works of refugee artists.

“Uprooted: The Art of Refugees” features six artists originally from Ethiopia, Iraq and Somalia. Through their work, they portray their home countries and their experiences in moving here.

When we think of refugees, we tend to envision a sea of tents, rather than individuals or the professional lives they left behind, said Allison Weiss, the museum’s executive director. In presenting this exhibit, “We’re trying to make a statement; we do this deliberately: Everybody is part of the community and we value what they’re doing.”

These artists, Weiss added, are contributing to our community through their jobs and their art; they are raising families who are growing up and contributing to making the community better. The exhibit takes us away from the sea of tents image and puts a face on the person behind each story.

Khalid Alaani, 42, came to the United States six years ago. “I left Iraq in 2006 because of the violence and stayed in Syria for six years,” he said.

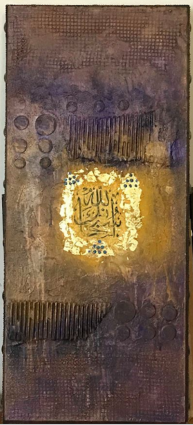

In Iraq, he was a pharmacist by profession and an artist by avocation. In Syria, he was welcomed into the art community and received papers to stay in the country legally for several years. Alaani’s art blossomed in Syria, where he developed his own style and started showing his work in galleries.

In 2009, Alaani was surprised to learn from the United Nations International Organization for Migration (IOM) that he had been accepted for immigration to the U.S. He went through three years of interviews and background checks before he was granted permission to enter the country. “The process is long, especially for someone waiting to start his life,” Alaani said.

The situation in Syria was growing worse, when, suddenly, an IOM representative called Alaani to say he could go to America in two weeks. Elated, “I started jumping,” Alaani recalled.

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) guided Alaani through his resettlement, with an orientation program on U.S. laws and customs and a case manager who helped him write a resume, find a place to live and a job, shop for groceries and with all his other needs. His first job was as a restaurant cook. Now Alaani is working a pharmacy technician while studying to get a pharmacist license. In February, he became a U.S. citizen.

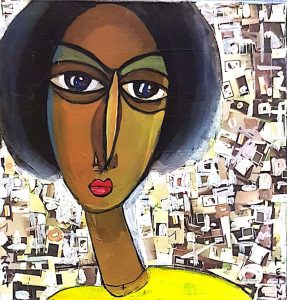

Alaani’s first two paintings in the exhibit, both painted in 2013, express his feelings about being a new immigrant. The first depicts a woman standing with dark, piercing eyes, expressionless, her hair blowing in the wind, unsure of what awaited her. In the painting hung alongside it, the woman is seated, holding an infant, also appearing somewhat uncertain, but with a calm expression on her face. A bright red cloud swirls behind her, the memory of what she left behind.

The woman is tired and worried, said Alaani. “Refugees experience a lot of challenges as well as opportunities.”

When people first arrive, they feel excited, then they start to worry about what they will do, what kind of job will they find, how will they take care of themselves, he explained. “I feel so close to those paintings. It’s what I felt as a refugee.”

Some of his 15 paintings in the exhibit depict women appearing comfortable in their new lives. But then there is one Alaani painted last year. It shows a woman holding a baby looking at a wall of barbed wire. “I was just doing what I felt,” he said.

Alaani typically carves out at least one day a week for his art. “Art is an endless process of searching and exploring, and, above all, pleasure,” he said.

Fetun Getachew’s work hangs in the collection of the National Museum of Art in Bahir, Ethiopia, but finding museums and galleries interested in displaying her work here has not been easy.

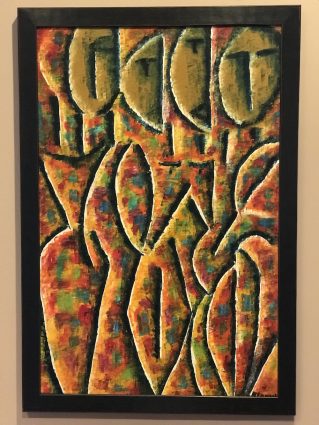

Getachew, 41, has 13 works in the show. Her canvasses depict colorful scenes of Ethiopian women; some are collages. One shows women in the marketplace wearing beautiful dresses made from grocery store ads. “I see the women’s faces; I know what kind of situation they’re in,” she said. “I look at a woman and I know her experience.”

Getachew was a wife, mother, artist and art teacher in Ethiopia when the political situation deteriorated in 2011. First, her husband was jailed. Then, after an art show, somebody came to her house to ask why one of her pieces said “Freedom.” Despite her lack of involvement in any political situation, Getachew feared remaining in Ethiopia.

When her husband was released, he went to India to work on a doctoral degree, and Getachew obtained student visas in 2011 for her and their 4-year-old son to come to the U.S. so she could study for a master of art degree at the Art Institute of Washington.

She struggled without the childcare and other support she would have had in Ethiopia, so she left school and appied to change their visa status to asylum. She worried they would be sent back to Ethiopia. Instead, she said, “the case worker said, ‘Welcome to America.’ I was happy.”

Getachew has sold her work at the Silver Spring Craft Market and had art shows in the area. Yet since she was unable to get a job as an art teacher and unsuccessful at opening an art school, she has worked at everything from dishwasher to a 7-11 clerk.

Seven years later, Getachew is in school again, this time at Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA). “Thank God, everything is getting better,” she said.

“Uprooted: The Art of Refugees” is on view through Sept. 2 at the Sandy Spring Museum, 17901 Bentley Road, Sandy Spring. Hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Thursday, Friday and the first Saturday of each month, and 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Sunday. Admission is free. Call 301-774-0022 or visit www.sandyspringmuseum.org.