The Bender Jewish Community Center of Greater Washington is a lively place on a weekday afternoon. Children laugh and chatter, moms mingle, holding their little ones by the hand, students settle in with laptops and iPads. In the adjacent Goldman Art Gallery, however, things are peaceful. The art on the walls there, an exhibit called “To Bear Witness: The Art of Testimony” is a quiet reminder of lives cut short and families impacted by the horrors of the Holocaust.

“They’re all local artists,” said Lisa Del Sesto, assistant director of arts and ideas at the JCC. “One woman submitted work on her mother’s behalf —she was a Holocaust survivor who was an artist in her lifetime but passed away.” The other nine artists — one a Holocaust survivor, eight children or family members of survivor s— are very much alive, and all plan to be at the JCC on Wednesday, Jan. 23 for an artists’ reception.

“We asked the artists to give us a sense of what their work is, how their work reflects the idea of testimony,” Del Sesto explained. “The thought behind it was that this artwork provides a visual testimony to the experiences of survivors, and the experiences of family members and next generations of survivors, so that, as Elie Wiesel said, ‘Everyone who meets a witness becomes a witness.’”

The exhibit, which runs through Feb. 23, is timed to coincide with International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Jan. 27. But for Silver Spring poet and visual artist Miriam Mörsel Nathan, remembering the Holocaust is not confined to one day a year. “It informs everything in my life,” she said softly. “My parents were Czech Jews. They were married in Prague in 1937, and then it started to be dangerous for my father to be there, as a Jew.”

He was Czech-born, she said, but from the east. “There was a possibility there would be a deportation.” Her father left Prague, saying he would be back in three weeks. Her mother attempted to get out as well, but didn’t make it.

“She ended up being deported to Terezin — Theresienstadt — in 1942,” Mörsel Nathan said, referring to the “hybrid” concentration camp/ghetto where, despite its reputation as one of the less deadly of the Nazi concentration camps, 33,000 Jews were executed and 88,000 were transported east to Auschwitz-Birkenau. “Terezin, of the places to be, was a better place, if there is such a thing.”

Mörsel Nathan’s mother had skills, “typing, stenography — and she was fluent in German and in Czech and was very proficient; that pretty much saved her life. She worked in the central office, typing lists of people who were being sent east to be killed. But because she was ‘good,’ they did not send her.”

In the meantime, Mörsel Nathan’s father was trying to stay one step ahead of the Nazis — in Italy, Greece, the former Yugoslavia and finally on a ship to the US. “He had been going from city to city, playing chess for food,” she recalled, “and he didn’t have papers for the U.S. , so when he arrived, they didn’t allow him to disembark.” The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) approached him with an offer: He could go to the Dominican Republic, where the dictator Rafael Trujillo was offering a safe haven for Jewish refugees in the remote agricultural village of Sosua. Stuck on Ellis Island, he jumped at the opportunity.

He was in Sosua when Mörsel Nathan’s mother sent a telegram to his aunt in Virginia: “‘Inform my husband I return.’” It took her a year to get from Terezin to the Dominican Republic, but she made it. The couple was reunited in 1946 — after seven years apart — and Mörsel Nathan was born nine months later.

Her artistic contribution to “To Bear Witness: The Art of Testimony” is not about her parents’ survival or their happy ending, however. “I had this box of photographs my mother had left with a friend who was not Jewish,” she said. “A box of photographs of people who were killed, for the most part.”

Mörsel Nathan “knew” of all these people — relatives she had never met, the aunts, uncles and grandparents who perished in the Holocaust — and her art depicts them, veiled and shadowy, lost to the tragic events they experienced, but never forgotten. The absence of these family members, this fragmentation of memory, has been as much as part of the family lore as her parents’ ability to survive.

“It was an interesting juxtaposition,” the artist said. “For my father, it was almost like a challenge and an adventure for him, even though his parents were killed, his two sisters were killed. I think they all were killed in Auschwitz.

“He suffered huge losses, but his story was more of this ‘how I survived’ in an adventuresome sort of a way. It became almost humorous to him.”

Mörsel Nathan’s mother remembered things differently. “She witnessed so much loss,” she said. “Her father died (in Terezin), she would tend to him, stepping over bodies and burning mattresses to comfort him, clean him and take care of him until he died. Her two brothers were sent east, so she witnessed that.

“She always wore a shawl of sadness.”

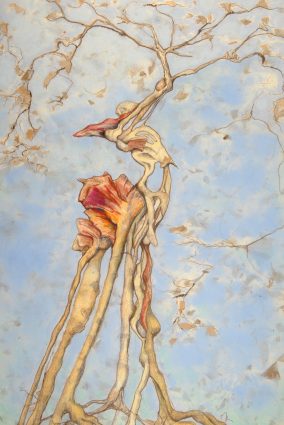

That “shawl of sadness” finds its way into the exhibit, even in the most vibrant and beautiful works of art. Del Sesto thinks that’s part of what gives “To Bear Witness: The Art of Testimony” its power.

“All of these works are deeply personal,” she observed. “It was a testimony of your memory, of your parents’ memory, of your experiences and the experiences you learned about from other family members.”

Along with their work Del Sesto asked each artist to explain “how this work ties back to their experience and why they feel it’s important.” Visitors to the exhibit can read a 100-word essay on the meaning of each piece, crafted by the artist to share their testimony even further.

“On a personal level, I feel like I brought these photographs out of the box,” Mörsel Nathan said. “I put them into a place where they can be seen, and the names can be said, and the stories can be told.

“I am the repository of those stories,” she added. “And if I don’t tell them, nobody is going to know.”

“To Bear Witness: The Art of Testimony” is at the Bender JCC, 6125 Montrose Road, Rockville through Feb. 23. Hours are 8 a.m. to p.m. Monday through Thursday; 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Friday and 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. Sunday. A reception with the artists will be held from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, Jan. 23. Admission is free. Call 301-881-0100 or visit www.benderjccgw.org/arts-culture-jewish-life/goldman-art-gallery.