Wrinkled, sepia-toned photographs depicting church socials, one-room schoolhouses and children at play outdoors; a small shovel that broke new ground; and a 65-year-old baseball uniform from the Scotland Eagles, the all-African-American team from the Scotland neighborhood in Potomac. These are tangible artifacts of three once-vibrant African-American communities in Montgomery County dating to the post-Civil War era of Reconstruction. It’s a history that’s more often ignored than celebrated or put on display.

The stories behind these distinctively African-American Montgomery County communities – two in Potomac, one in Bethesda – are fraught. “Plans To Prosper You: Reflections of Black Resistance and Resilience in Montgomery County’s Potomac River Valley,” a new exhibit on display through Aug. 11 at the American University Museum in the Katzen Arts Center, tells an affecting and still resonant history of these seminal African-American communities. Amid struggles and efforts to eliminate and redevelop their land, the stories of those who lived as minorities in these small community pockets represent moving examples of faith, family and fellowship. The exhibit’s title, “Plans To Prosper You,” comes from a passage in the bible’s book of Jeremiah, indicating the staunch connections to the churches that stood at the center of each community.

“It’s an ugly history and it’s swept under the rug, precisely because it doesn’t benefit the people in power to know about it,” noted Adrienne Pine, an anthropology professor at American University who oversaw the cross-disciplinary team of anthropology, art history and museum studies students on this year-long project. Pine sent 11 graduate students in her foundational anthropology course to visit and study Scotland and Tobytown in Potomac and the River Road community in Bethesda, historically black enclaves surrounded by predominantly wealthy white neighborhoods.

“How do you basically take documentation and field work of a neighborhood and a historical situation and make an exhibition out of it,” said Jack Rasmussen, director of the university’s art gallery and a professor of curatorial practice. “We’re not showing art, per se, which is usually what we do. We’re really presenting ideas and histories and social problems.” In the exhibit approximately 75 tangible items — artifacts and photographs, loaned by community members and their descendants — illustrate this history.

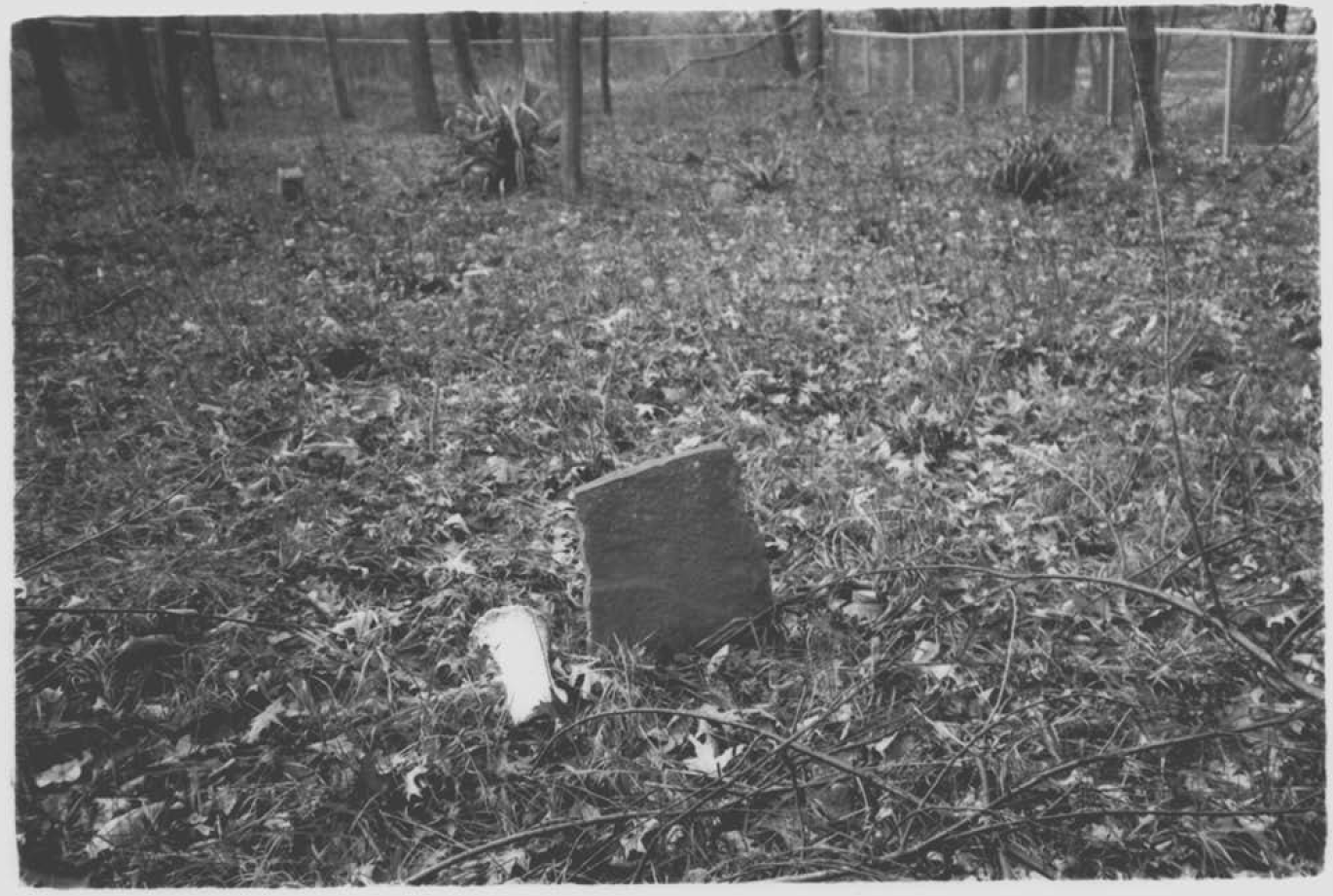

Delande Justinvil, a doctoral student in anthropology and one of the student curators, explained that the team’s research began by exploring African-American cemeteries in the county, which led them to the still-thriving community of Scotland off Seven Locks Road in Potomac; the Macedonia Baptist Church, which is the remaining remnant of the River Road community, its historic cemetery literally paved over in the late 1950s to make way for the Westbard development; and isolated poverty pocket Tobytown, which was founded in 1875 and today has about 60 residents; most are descendants of freed slaves. “As we got more involved and began doing more ethnographic research and speaking to more community members,” Justinvil said, “we learned about the issues of disenfranchisement surrounding these burial grounds [but we saw] there are much greater issues than just the cemeteries.”

He and his classmates examined old maps dating back to the 1870s and newspaper obituaries to discover family names that might otherwise have been lost – Randall, Genus, Davis and Dove — names on maps, but also more. These names indicated that African-American farmers and day laborers owned and farmed their own plots soon after Emancipation and well into the 20th century. Justinvil pointed to one obituary on display that mentions the Macedonia Moses Cemetery as proof that the contested burial ground in Bethesda existed, even when county leaders and developers wanted to zone the land for commercial use and discounted that there was a cemetery. In an oral history interview last fall, Harvey Matthews, a longtime member of the Macedonia Baptist Church, recalled playing hide-and-seek between the cemetery’s gravestones as a boy.

[foogallery id=”40522″]

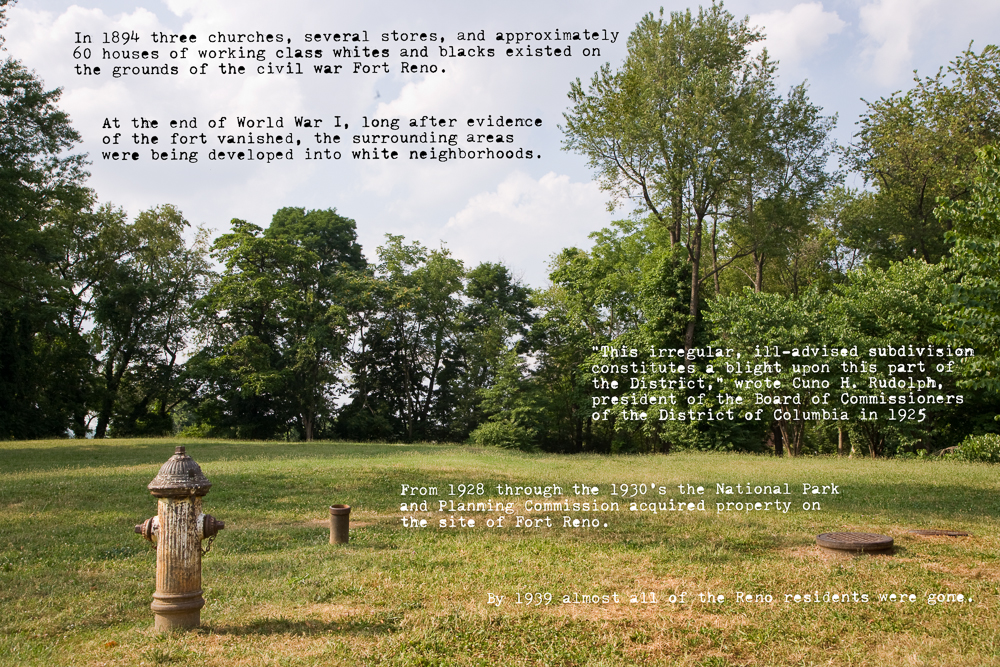

“There’s a history of these strong communities being forcibly displaced through a variety of mechanisms,” said Pine, “through deceit, force and the willful denial of public services.” She noted that well into the 1950s, for example, Scotland had no public water and sewer infrastructure. County inspectors threatened evictions citing substandard living conditions. A ploy, the professor said, for developers to redevelop the desirable land parcels tucked into a wealthy suburban enclave. But the tightly-knit community’s residents organized and spoke out; the Save Our Scotland (SOS) campaign kept the community from being torn down by developers. This history was documented by county resident Alan Siegel, who took about a thousand pictures of SOS meetings, protests and daily life in Scotland in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Justinvil was excited to discover a box of Siegel’s photos, along with nearly 1,000 negatives in Montgomery History’s archives. “Many of the photos had not yet been cataloged,” he said. Siegel’s photos of the county planning commission, the SOS board, rallies that called attention to the community’s plight as well as pictures of people at home in the Scotland neighborhood show the active life of Scotland residents.

[foogallery id=”40527″]

Pine was stunned by a loan from Scotland descendent Deborah Young: the complete 1954 Scotland Eagles baseball uniform, including the glove, cleats and bag, worn by Young’s father Dennis when he played shortstop in the regional Negro baseball league. “Baseball was a way to take a pause from the ills of societal racism and classism, and a time to come together with community and family,” wrote anthropology doctoral student E. Nickole Sharp in the exhibit catalog. Similar to the pride of place the community’s churches and segregated schools had, weekly baseball games were a another means to unify people from these small isolated enclaves while they also had fun and mingled.

The goal of the project – beyond introducing students to ethnographic research practices — was to shed light on a local population that has long been overlooked, disenfranchised, even erased from history books, said Pine, the professor. “Those communities are at the core of our work …. They’re the ones that we as researchers are most beholden to.” She and her students want to represent them with dignity and accuracy. “They’re the folks who have been written out” of history, she said. “This is for them to see their own histories and their own culture presented through their eyes.”

But she hopes another audience will spend time perusing the maps, photos, collages and artifacts from Montgomery County’s past. “The exhibit has this larger purpose of helping share this story with other people, including those who have participated in the erasure of the histories of these communities, to ensure that they can’t be erased going forward, metaphorically or physically.”

“Plans To Prosper You: Reflections of Black Resistance and Resilience in Montgomery County’s Potomac River Valley,” through Aug. 11 at The American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, 4400 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. Hours are 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday. Admission is free. A gallery talk is set for 3 to 4:30 p.m. on Saturday, July 20; RSVP at: tinyurl.com/aumuseumkatzen. For information, call 202-885-1300 or visit www.american.edu/cas/museum.